Leveraging Islamic Finance to Support Indonesian MSMEs Through the Covid Pandemic

Worldfinancialreview.com – (29/1/2022) In a recent statement, Perry Warjiyo, the governor of Indonesia’s central bank, highlighted both the importance of MSME’s to the Indonesian economy, as well as a need to support them through the coronavirus pandemic.1 When combined with global best-practice, Indonesia’s unique Islamic financial ecosystem represents an invaluable toolkit for supporting these businesses through the pandemic.

Indonesian law No.20 of 2008 specifies that an MSME is any business that holds less than 10 billion IDR (roughly $700,000 US) in assets or has annual revenue of less than 50 billion IDR ($3,500,000 US). In more illustrative terms, the label of MSME applies to everything from an owner-operated market stall to a medium sized construction firm.

According to World Bank data, the Indonesian poverty rate sits just below 10%, and marginal poverty reduction has become more difficult the lower that rate falls. With the most recent data from Indonesia’s Ministry of MSMEs suggesting that MSMEs provide just under 97% of national employment, these businesses are critical to any long-term poverty reduction strategy.

Despite their value to the Indonesian economy, MSMEs have taken a hit from the recent pandemic. Public health issues have placed constraints on demand for their services, particularly for MSMEs in sectors such as tourism or hospitality. Over 60% of micro- and small enterprises surveyed by Indonesia’s national development agency (BAPPENAS) reported a need to change the way in which they sell goods. Additionally, MSMEs in Indonesia are disproportionately reliant on domestic demand. Despite accounting for over 60% of GDP in 2019, they provided only 14% of non-oil export revenue, according to data from the ministry of MSMEs. These factors mean that Indonesian MSMEs will likely need support for as long as Covid negatively affects domestic Indonesian markets. It is therefore unsurprising that 25% of micro- , and over 30% of small and medium enterprises surveyed indicated the need for additional financing to survive the pandemic, according to BAPPENAS.

Indonesia’s Islamic finance ecosystem

The proposals for supporting MSMEs in the next section will rely on implementing institutions with a regulatory climate largely unique to Indonesia. Below is a brief overview of the two categories of implementing institutions that are critical to these proposals: rural Islamic banks (BPRS), and Baitul Maal wat Tamwil (BMT).

FjakartIslamic banks in Indonesia function similarly to their secular counterparts but are constrained to the use of non-sharia compliance instruments (that include non-interest-bearing contracts), and investment in halal sectors. Moreover, a new law is being introduced requiring all banks in Indonesia to commit a ratio of their portfolio to providing microfinance, or financing MSMEs. These lending requirements, known as the macroprudential inclusivity ratio, are set to increase from 20% in June 2022 to 30% in June 2024. It is important to note, for the next section, that funds channeled through a microlending institution count towards a bank’s obligation under the ratio.

Compared to banks, the regulation of BMTs is far less clear. This is a result of the BMT’s dual function of community banking and social finance. A BMT is responsible for both providing Islamic microfinance products to a surrounding community, as well as the collection and disbursement of obligatory (zakat) and non-obligatory (infaq, shadaqah and waqf) Islamic charitable donations. Aside from donating zakat as a gift, a BMT can use zakat donations to provide charitable loans (qard-al-hasan) to MSMEs, provided the loans are non-interest bearing and collateral-free, the business is in a halal sector, and the owner of the enterprise falls into one of eight categories of eligible zakat recipients (asnaf). Whilst it is true that Islamic banks also provide zakat collection and disbursement services, they have far less latitude in zakat disbursement than BMTs. Under Islamic Jurisprudence it is also permitted for the administrative costs of zakat disbursement to be covered by donations.

Reviving MSMEs through digitalization

In a forum hosted by the Islamic Development Bank, Malaysia, one of Indonesia’s largest neighbors, has provided replicable policies for supporting MSMEs through digitalization. Learning from this example, an Indonesian digitalization program that focusses on MSMEs and utilizes Islamic banking institutions would have three components: a subsidized e-commerce platform, training for transition to online business, and support for online marketplaces for microfinance.

Currently Indonesia hosts several privately run e-commerce platforms for MSMEs, including: Tokopedia, Shoppee, Lazada and Bukalapak. Whilst these platforms provide alternate avenues for MSMEs to market their goods (a service greatly demanded, as seen above), they charge a fee for their use. This squeezes the profit margins of MSMEs in a period where rising unemployment and reduced economic growth are already suppressing demand. A subsidized government platform, without fees, can be justified on two grounds. Firstly, it will advantage micro- and small-enterprise owners, a group disproportionately found in low-income regions.2 Additionally, by moving to e-commerce, MSMEs are reducing negative health externalities, a public benefit which should be rewarded by the government.

One of Indonesia’s largest neighbors, Malaysia, has found success in sustaining MSMEs during the pandemic through efforts to shift pre-existing MSMEs onto e-commerce platforms. This required a significant training component for entrepreneurs, one that was carried out largely online, by the Malaysia digital economy corporation (MDEC). According to MDEC, feedback from the program suggested that this mode of delivery was still successful in transferring key skills to participants.3 Given the benefits that online teaching brings to scalability, not to mention public health, this program provides a blueprint for Indonesian policy makers.

However, the question remains, how does this relate to Islamic finance? The BPRS and BMT in a community have significant social and economic ties to the entrepreneurial sector in their area. By leveraging these connections, it will be possible to advertise these services to a greater number of people and support this process by providing financing to MSMEs. For instance, a BPRS or BMT could over the cost of online training, in exchange for a share of the business future profits. This instrument is known as a al-mudarabah al-muqoyyadah in Islamic finance.

Finally, online financing marketplaces will provide an avenue through which BMTs and BPRS’ are able to continue lending operations through public health restrictions. There are two ways in which this would occur. Firstly, institutions holding an excess of loanable funds (due to disruptions in lending operations) would benefit from an online platform that will allow them to connect with MSMEs who need additional financing. Secondly, it is also the opportunity for the use of zakat in this area, as, under certain circumstances, the use of zakat in refinancing loans for those in arrears is permitted under Islamic jurisprudence. It should be noted that for zakat to be used in commercial refinancing, the loan must be collateral-free and non-interest bearing, and the recipient of the loan must be personally in arrears. This suggests this source of financing is mostly available to micro-enterprises.

Improved temporary financing for MSMEs

As highlighted above, between 25% and 35% of MSMEs require additional financing to support themselves through the pandemic. In addition, according to the same survey conducted by BAPPENAS, over 30% of small and medium enterprises have had to reduce salaries to survive the pandemic. These results suggest that additional financing is required if the Indonesian economy wishes to retain the wealth and employment that this sector brings.

There is a possible supply of loanable funds, especially in larger urban Islamic banks, but it is difficult for these banks to assess loans to MSMEs, especially micro-enterprises and MSMEs operating in rural areas. One reason for this is that many rural loans are assessed with reference to the character of the borrower and require significant local knowledges. For instance, at one regional bank visited by the authors, many of the loan officers also work as teachers at local schools, and many of the borrowers are local parents. A key institutional advantage of BMTs and BPRS is that they engage directly with rural communities, and that their lending officers often are personally and socially connected to prospective borrowers.

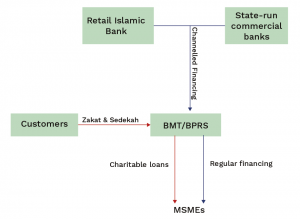

Below is a proposed financing model that combines the relatively large supply of loanable funds from private Islamic banks and state-run commercial banks, and the reach and lending expertise of BPRS and BMTs.

This proposal is a way for the larger urban Islamic banks, and state-run commercial banks, to channel funding through the BMTs and BPRS to MSMEs. The first channel for funding is the use of a two-leg Islamic debt instrument. Firstly, the state run commercial banks, and Islamic retail banks enter into a conditional profit and loss sharing agreement (al-mudarabah al-muqoyyadah) with an intermediary institution (in this case a BPRS/BMT). This contract specifies that the money put in by the larger bank will only be used in lending to a specified group of MSMEs. For example, MSMEs in particularly affected sectors such as tourism, or MSMEs below a certain amount of revenue. The intermediary then identifies prospective MSMEs for new loans, and enters either a cost-plus-financing (murabaha) or a profit and loss sharing (mudaraba) agreement with the MSME. Finally, the profits from the loans made by the intermediary are split at a prearranged ratio with the financing institution. This can get a little confusing, but fundamentally, the intermediary is engaged to lend on behalf of the larger institution, and is rewarded with a share of loan profits in exchange for their lending expertise.

The second funding channel, where zakat and shodaqah collections are used to provide charitable loans (qardhul hasan) as refinancing for MSMEs in arrears, is more direct. However, this financing method is much more tightly regulated than the first, and, it bears repeating, the legitimacy of the loans is predicated on the personal financial situation of the business owner. Despite this, the use of qardhul hasan as a method of zakat disbursement (as opposed to the use of transfers) has one key advantage: by having zakat recipients repay the principles of their loans, a zakat fund based on charitable loans is theoretically self-replenishing.4

This is in essence a developmental policy, which necessarily begs the question, what’s in it for commercial banks? In answering this question, it is perhaps helpful to divide fully private Islamic banks, and state-run commercial banks into two separate cases. State-run banks present an easier case, as they remain a key policy instrument for state governments that have little discretion over their expenditure. As for privately-run Islamic banks, this financing structure presents an attractive opportunity for them to meet their new obligations under the macroprudential inclusivity ratio. Whilst there are no publicly available data on their current progress towards achieving the ratio, recent lobbying to delay or relax new regulation would suggest that meeting these new requirements will require a significant adjustment to banks’ loan books.

Conclusion – hurdles and opportunities

As we’ve heard countless times, the coronavirus pandemic brings unprecedented economic challenges. This is certainly the case for MSMEs, who have had to deal with suppressed demand, restricted supply chains, and the need to innovate in the way they do business. Nevertheless, MSMEs remain critical to achieving Indonesia’s goal of long-term, equitable growth. The measures to support MSMEs that have been proposed in this article fall loosely into two categories.

The first is a push towards the digitalization of MSMEs, involving a subsidized ecommerce platform, training for digitalization, and an online funding platform. By using BMTs and BPRS as a one stop shop for implementation, this policy will be able to reach a larger number of MSMEs, particularly in rural areas. It is unclear if these smaller institutions have the human resources to help administer these programs, but if they can overcome this challenge, it provides a significant chance for Indonesia to continue its push for poverty alleviation.

The second arm of the proposal, temporary financing, functions much more within the standard operations of the Islamic financial institutions. There is a concern that it will lead to too much money in the hands of smaller institutions, and a resultant decrease in loan quality and performance. We believe this to be overstated, and the risks will be far outweighed by the benefits it will have on rural incomes.

Although they can be implemented separately, these proposals are by no means mutually exclusive. Through the parallel implementations of strategies proposed above, MSMEs will be better equipped, financially and operationally, to deal with whatever challenges may arise from the pandemic.

About the Authors

George Vamos is a final-year student at the Australian National University, studying Politics, Philosophy and Economics. He is working as an intern with CORE Indonesia.

Ebi Junaidi is currently Director of Islamic Economics and Finance for Center of Reform on Economics (CORE) Indonesia. He is a lecturer at Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Indonesia. His research interest is on Islamic social finance, Waqf, Risk and Time Preference and Financial Decision.

Azhar Syahida is a resercher at CORE Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia. He is interested on economic history, SMEs, and regional economics.